Ese

Large language models are better thinkers than writers. OK—they don't think as humans do, but I've still let it write the vast chunk of my computer programs over the last year or so. That is a task which demands a reasonable amount of cognitive effort and critical thinking from human beings.

I also use them as writing aid—a thought partner that will poke holes in my logic, correct my structure and challenge my assumptions in what I write. These also need a good think from typical humans.

Yet, you will not see any AI generated text in this blog without sufficient disclosure. I will pay the costly signal for you to know that I spill words on here that have long fermented in my mind. If I post AI generated text here, how can I prove that all those extra words that are extrapolated out of my prompt are something that I have read and taken ownership of?

I regard meaning to be terribly sensitive to every word—how we vocalise them, the culture they are rooted in, their rhythms, and how they are situated amongst the words around them—can all have a powerful bearing on what gets conveyed. I'm going to heavily defer to the great late William Zinsser,

Master the small gradations between words that seem to be synonyms. What’s the difference between “cajole,” “wheedle,” “blandish” and “coax”?

and his appreciation for how the feeling-tone and thus the meaning of words is affected by the sounds of words and sentences,

E. B. White is one of my favorite stylists because I’m conscious of being with a man who cares about the cadences and sonorities of the language. I relish (in my ear) the pattern his words make as they fall into a sentence. I try to surmise how in rewriting the sentence he reassembled it to end with a phrase that will momentarily linger, or how he chose one word over another because he was after a certain emotional weight. It’s the difference between, say, “serene” and “tranquil”—one so soft, the other strangely disturbing because of the unusual n and q.

and finally this statement, an unintentionally wistful statement in the age of slop,

Remember that words are the only tools you’ve got. Learn to use them with originality and care.

If I generated large swathes of text via machine intelligence and then chose to claim ownership over its output, I'd be dishonest with myself—the subtle, granular string of words that give life to meaning would have been delegated to a brilliantly loaded dice roll. At best, I could only claim a coarse agreement with what came out of the machine.

It's not new for the average person to belabour themselves over every word that spills out of them. We are handed words and phrases to use by our culture, institutions and systems of status-assignment.

Journalists are pressured to speak journalese.

In a shock move, Bangalore man sets up a firestorm of controversy after he lamented the linguistic collapse amidst slop production woes.

Academics are made to speak acadamese.

This essay interrogates the discursive interventions of a Bangalore-based actor whose recent problematization of linguistic degradation within content production ecosystems has catalyzed significant contestation among stakeholders. We argue that such meaning-making practices must be situated within broader frameworks of late-capitalist semiotic entropy.

Closer to home, there's corporatese.

A Bangalore thought leader has ignited dialogue around linguistic excellence amid content pipeline challenges. We're taking these learnings on board as we iterate toward quality.

Few communicate like this authentically. I want to not just draw attention to the clichéd nature of these sentences. I'm gesturing at the mechanism where a writer is lifting off-the-shelf, fast-food verbiage that allows them to circumvent the pain of articulating their thoughts with precision and give them clarity. There's no AI generation involved in these jargoneses, only a feedback loop where the prevalently accepted writing styles block out original channels of thought.

AI-ese comes from a different place than the other jargoneses. Instead of ambiently surfacing from a specific subculture, they are coming from a machine that has compressed massive amounts of textual content and provides fast-food verbiage for all walks of life. There is slop everywhere today.

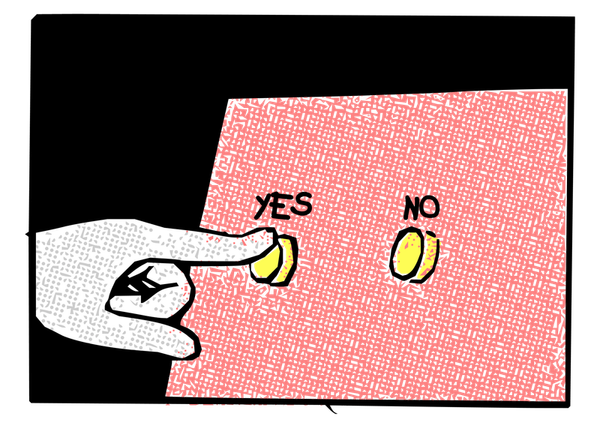

This proliferation of AI-ese seems to pierces through every cultural bubble, making the aforesaid feedback loop of "language collapse" global and omnipresent. Because of this, I don't think it's fair to call this AI-ese. This is just ese, for it engulfs everything.

This isn't just frustration—it's a catalyst for broader discourse. A Bangalore-based individual has sparked vibrant conversation around linguistic integrity, and the response has been both complex and resonant. What emerges is not merely critique, but an invitation to reimagine how we engage with the written word.

Social media feeds, news articles, press releases, and notably, even 1-on-1 correspondence in email and messaging apps are getting slopified.

There used to be interstitial spaces between the contexts of work and status-driven communication where people truly spoke their words—imperfect words, but their own words. My observation is that the self-words in these interstitial spaces are in rapid decline. The subtle craft of articulation will make way for the craft of figuring out which loose structures of meaning from the Great Inscrutable Machine must we align with.

When [Walter J Ong] began his studies, "oral literature" was a common phrase. It is an oxymoron laced with anachronism; the words imply an all-too-unconscious approach to the past by way of the present. Oral literature was generally treated as a variant of writing; this, Ong said, was "rather like thinking of horses as automobiles without wheels."

[...]

It takes a few thousand years for this mapping of language onto a system of signs to become second nature, and then there is no return to naïveté. Forgotten is the time when our very awareness of words came from seeing them. "In a primary oral culture," as Ong noted, the expression "to look up something" is an empty phrase: it would have no conceivable meaning. Without writing, words as such have no visual presence, even when the objects they represent are visual. They are sounds. You might "call" them back—"recall" them. But there is nowhere to "look" for them. They have no focus and no trace.

— The Information, James Gleick

I sometimes wonder if the effect of AI generation on writing, the way writing itself had an effect on orality. A pre-literate culture had a different relationship to language and communication that is mostly inconceivable to us today.

Maybe language models will become good writers some day. Maybe, we will realise that it's way too convenient to have a machine arrange the words in our head, and that the structural unit of communication is not an individual word, rather, it is a prompted generation.

Maybe, humans will have their cognition merge with that of language models. Maybe, it's already happening as we speak.

This post is a follow-up to Rude Slop Behaviour, but it can be savoured on its own.