Universities are a place of innovation and exploration, thought childhood me. What a chump. Sappy son of the sunny season. Someone should have told him Universities will systematically slaughter curiosity much like school did. Only more snobbish. They believe they are at at the forefront of innovation by teaching you materials ripped off from guru99.com and geeksforgeeks.com.

Regrettably, no one told me. Except some of my friends from other colleges who got deceived at the same time as yours truly.

Engineering colleges in India are more often than not, terrible vocational schools, and a marketplace to sell parents the promise of a degree and placements.

I almost resigned myself to becoming a cynical grump with a chump stamp on my forehead. Until I found hope.

An ex-college club

It was right after the end of my first year. I was scrolling through the list of clubs maintained by my uni. PES Open Source. Oh, I love the idea of Open Source. Open Source people are tinkerers. They don’t debase learning, nay, they actually revere it.

PES Open Source was dead. The group was exquisite when alive. They operated out of the dark ages of 2011 AD, when Open Source was not a buzzword to pad out your résumé with. Which means most students and faculty had no idea what these nerds were even on about.

These people loved learning, the bottom-up kind that resulted from tinkering. It’s telling that one of the first things they did when they formed was to bunk a week of college, so that they could attend a KDE conference in the city. They met the KDE leadership. They pushed themselves in ways college simply could not.

I was savouring the old records of the countless impeccable things that happened in their five year history. Colleges can have real learning somewhere. Student-led communities are the antidote to the scholarly numbness that colleges inject in our veins.

I found a link to their Slack workspace. I thought it was dead. But I clicked anyway.

PES Open Source was dead. Their founders not dead.

The founders were surprised at this blip of activity. They told me more about their golden days. I asked them if I could restart the community. They handed me the keys to the accounts.

Over the next two years I joined a rollercoaster with a set of like-minded collaborators. We tried to rebuild a community focused around Open Source. More importantly, around bottom-up learning. The kind whose members would be tinkering and sharing with each other ideas that excite them. We’d achieve a sum greater than our parts. This is my story of what that looked like.

Career or nothing

It didn’t make sense to try recreating the lightning-in-a-bottle that was the old group. Once that cohort graduated, there was no PES Open Source (not for long at least). We wanted something more systematic, and accessible. Let’s educate the masses about what Open Source really is like. Let’s learn to contribute ourselves. It’ll all be perfectly crunchy apples, cold and sweet.

I wanted this utopia. My collaborators wanted this utopia too. Open Source everywhere with all the students. Boundless learning and innovation.

I did not take into account that most students want other things. They were not sappy sons and daughters of the sunny season. They primarily wanted what the University dished out—the degree. My University existed not to be a beacon of light to enlighten a community of scholars, no. They were here to fulfil an economic demand. A piece of paper that helps you secure a job. Placements. Crack the interviews. Study in our system, and you get a stable career. Ideally one with a steady, overflowing income, that brings pride to your family name.

The marketing departments of the University revolve around targeting these pillars of Indian society.

The much romanticised college life, has a dark undercurrent. It permeates every activity. Every interaction. The air reeked of it. Life is about career. This is where you make your career. Every single action you make will either work towards your career or it won’t. This is where one’s authenticity is supposed to die so that they can finally transition to becoming a grown-up.

I like a good career, but I like being myself more. I like learning new things more. They can coexist with my career, without being sacrificed for it. These are statements I can make, because I am economically and socially privileged. I am aware not everyone is in a position to be able to adopt this line of thinking.

These career-or-nothing attitudes though, are often at odds with our philosophy.

Like when we adopted a non-hierarchical organisation structure. There is a core team to handle administrative tasks. We made it clear that this core team has no elevated status—they are just volunteers that moderate discourse, make our weekly meetups happen, and encourage projects. We also prided ourselves in being open and welcoming. Anyone interested can join and volunteer, with no interview process (which is the norm in college clubs).

We got a lot of people who applied to be the administrative backbone with incompatible motives. A lot of them did not understand Open Source software (not a prerequisite), but they sure as hell pretended to love it. Many people did absolutely no work, especially when we desperately needed it. They contributed nearly nothing, but were forthright in mentioning how they were a “core member” of our student society in their LinkedIn pages.

Silence is a liability

In addition to the administrative backbone, we wanted to cultivate a culture of tinkering among all the participants in the community. I was also aware that a lot will join and do nothing. We students have a tendency to put our foot in everything, act on nothing, and still have plenty to show for it. That’s how we were conditioned. So I introduced a simple measure to weed out large swathes of loafers. To get the PES Open Source Slack link, you had to take three steps.

Step 1: Fork the repository pesos/members-list on GitHub.

Step 2: Add your name, and introduce yourself in the text file.

Step 3: Open a PR against the main repository. A bot gives you a link.

We made it as beginner friendly as possible, with clear instructions, and a contact point for help.

This tiny barrier was effective enough to prevent a major chunk of students from mindlessly clicking a join link and forgetting about it. The bonus is, this was technically an Open Source contribution, the first for any beginner. By the time they join, they have already got the gist of how Open Source basically works.

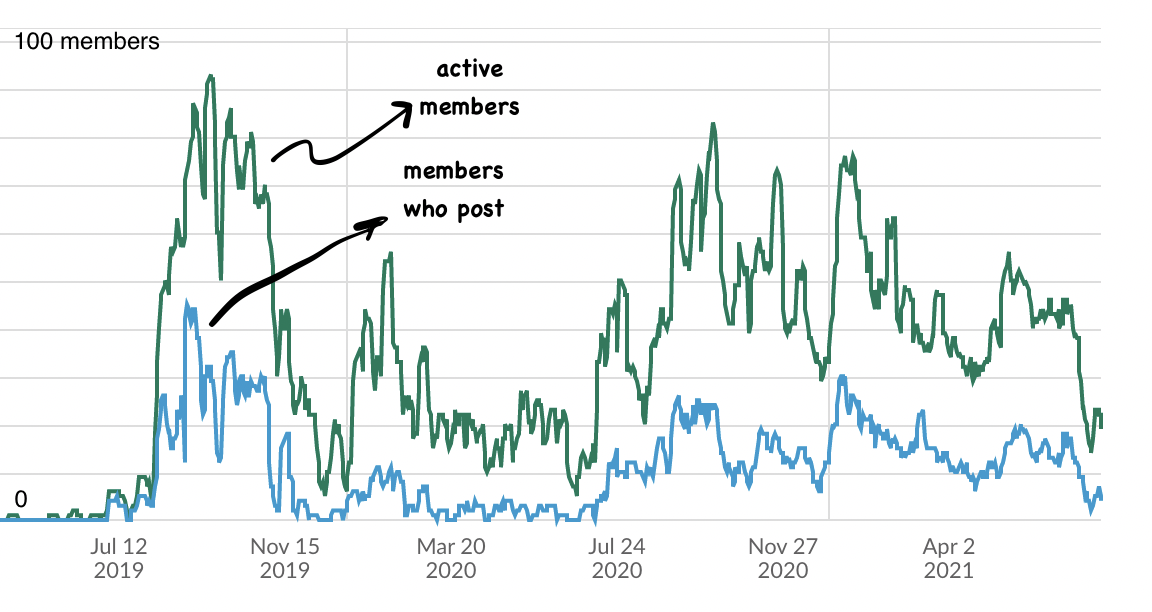

It wasn’t good enough though. In our efforts to make things accessible, we lost out on real participation. Forget enthusiastic participation, hardly 20-30 of the 293 that joined in our workspace even spoke a word on the community chatroom, when you look at the weekly statistics. The accessibility was in fact, a façade. Our physical meetups looked rather empty for a group that boasted such a large membership.

Here’s the problem. No one wants to participate in a chatroom where most of the members lurk, but do not speak. Silence begets silence. It doesn’t help that only this one tiny group of regulars talk, and it’s often about more advanced things. They appear as an “elite class”. So we end up psychologically blocking out people who could bring something new to the table, because they don’t feel welcome in the discourse.

We learned that there is a cost to every silent and inactive member that joins our community, which increases over time.

The physical meetups

PES Open Source was always more than just a chatroom. We also tried to have two meetups every month. The goal was to talk about things we find cool, showcase our projects, and really, just meet to learn from each other. We wanted to hear from a diverse set of voices from different areas of interest and experience levels. That did not happen.

Inevitably it always fell upon my main collaborators and me to come up with something, and share things we learnt. We tried hard to encourage activities that requires more participation from the people who show up. We wanted other people to start speaking up.

But no. People used to come, and expect to be lectured. In the classroom we borrowed to conduct these meetups, the front benches remained empty. The ones at the back were packed with blank faces. Maybe two or three got what a meetup really meant, and enthusiastically participated. Others could not digest the fact that the hierarchy was peer to peer, not headmaster to student. Even directly addressing them did nothing, they used to just shrug and mumble a phrase or two. They contributed nothing, during the meetup or outside of it. I was awestruck. Why do these people even show up, when they are clearly not interested?

Despite the awkwardness, the meetups were great in making those who participate feel like a community. The ones that did get something out of it, made the best parts of PES Open Source happen.

Ugh

Our biggest event in terms of raw numbers was during the month of Hacktoberfest. We thought riding this wave will make casual Open Source contributions and sharing ideas among students the norm. So we hosted a local Hacktoberfest physical event. It was our first and only somewhat large scale thing we pulled off. It had three events: A Git workshop, a day of talks from FOSS community leaders from the city, and a “hack day”.

It had a lot of the staples you see in any hackathon these days: stickers and merch everywhere.

The schedule was tight because of college exams getting in the way. We needed to borrow the University’s auditorium for 6 hours to have the “hack day”, where we get people in a room to work together and make small Open Source contributions all over the world. We’d be introducing a lot of students to Open Source.

The University buried us in layers of red tape, just to let us reserve the auditorium. They have a paper register where we reserve our slot. Except they have two paper registers. So another club booked the slot, on the other register. Oh and also, the word “reserve” is a loose term. We had to reschedule our dates every two days, because some other clubs that were created by faculty, just overrode our reservation, without directly telling us.

I was once summoned by the chairperson and this other faculty who ran the cybersecurity club. He wanted to interrogate me. He first looked me in the eye, as though I was supposed to confess to something.

“Sir, uhh, what can I do for you?”

“Hmm,” he said, with the gears turning in his brain, “what is this Hacktoberfest?”

I explained to him what Hacktoberfest was about.

“We are doing a CTF event on the same day. We cannot have another hacking-related event from someone else on the same day.”

“Sir, I think you are mistaken. Hacktoberfest has nothing to do with that kind of hacking or cybersecurity. We are not competing with your event. The timings do not clash, and the audience is different.”

“I still cannot have you do this on the same day.”

I was trying hard not to laugh, but I was also so tired of all this nonsense. We finally had to pick a Sunday in a four day long weekend, when absolutely no one would normally show up to college.

Promoting the event was hard as well. I vividly remember spending around ₹4000 from our allocated budget to get a giant promotional poster for our event near the front entry of our college. There was construction work going on in the campus, and the authorities were happy to dig a hole where our poster used to be erected, and throw the poster away with while they are at it. Well, at least we got 40 minutes of display time.

We still managed to get some Open Source leaders and tinkerers from our local community to give talks, ranging from Open Source hardware to philosophy. To this day, I am still happy with getting Zainab Bawa, CEO of HasGeek, to give a talk for us, who brought with her a memorable discourse.

The swag hunt

The hack day event, was fun, but had a disastrous outcome. We had rewards given to people who made the most contributions, the best contributions, etc. And obviously free stickers for all those who showed up. Of course, there were also the free t-shirts that come from Hacktoberfest itself.

We tried to be responsible hosts, emphasizing why Open Source is awesome, and what is good etiquette when approaching projects. We also tried inviting an Open Source startup and maintainers of a popular Open Source project to address the audience (the startup folks misread the date, and did not show up). Me and a lot of my collaborators were guiding people who were stuck.

We had also had a team to actually audit the contributions that were being made. There were about two hundred Pull Requests opened by the end of the event. Only about ten of them were legitimate. The rest of them were more or less spam or junk.

All that proselytizing and tireless efforts to build an Open Source community only to end with us hurting maintainers of projects around the world with spam. I was in denial about this for almost a whole year.

Our college happened to be ahead of the curve in this aspect, for there was a whole media debacle that followed in next year’s Hacktoberfest around spam Pull Requests made by college students just for a free t-shirts, and the opportunity to pad their résumé with “Open Source contributions” to impress recruiters.

I want to re-emphasize one point here. The people who behave in these ways are not bad people. They don’t have malicious intent. The problem is cultural and systemic, and to this day I have no solution, other than to keep doing what’s right, and keep being honest and passionate. Authenticity and philosophical consistency can be infectious.

Finally something that works

The Hacktoberfest nonsense burnt me out, and put me off PES Open Source for several months. I was not even doing something so radically against the grain, and yet everything felt almost purpose-built to sap our energy.

But a few months later, we slowly felt the pull to make our community work again. A bunch of our members started pitching ideas for Open Source projects. Past efforts for this never really took off, because my collaborators (the only ones taking initiative) were too busy to be hacking on projects. Now that there was nothing going on, they started making fun little Open Source projects, designed to be contributor friendly.

We could individually mentor people wanting to break in, and give them a space where it was okay to get things wrong. We made special help channels for these projects, so that the maintainers can help them learn the codebase and guide people. Even though we did not get masses of people participating we didn’t care because it was so much fun.

These little projects did well. Slowly, but surely, a new batch of juniors started making contributions. What really surprised us was that many of these projects started getting a bunch of external contributors from around the world as well.

We made these projects front and center for PES Open Source and they are doing fairly well. They are not “serious” software to drive a product or a business (despite having users, and one being showcased in a conference), but they are really fun to work on and learn new things. The maintainers of these projects are of course, my regular collaborators who have done a great job of making these friendly to beginners, yet technically interesting.

Killing PES Open Source

We realised we do not want to be big, or to throw big events. Most of the great stuff was coming from a small set of passionate people. Most of the learning happened in this small group, who cared about our ideals.

We want people to network and develop a sense of belonging. We need people to know all the other people. That’s what a friendly-neighbourhood community is, no?

Through other outlets, I started talking to and finding people with a tinkerer’s mindset who share the same values that we did, from universities all over India. There were always such students found in obscure pockets and little bubbles.

I was starting to arrive at a set of guiding principles for a new community, based on our experiences. They were:

- Non-participation is a liability.

- Connecting a diverse set of people with shared ideals is a superadditive function. One plus one is more than two. Creating innovation is non-linear with the number of effective connections we make.

This coincided with me being influenced by Nassim Taleb’s “Antifragile”, without which I won’t even have the vocabulary to say what I was really trying to build with our Open Source community. We used to run our projects in a centralized way—meet our specifications so that we can standardize, and make it easier for new contributors. This is nice, but it constrains the ability for chance events that may benefit us, yet do not fit in our framework.

I pitched a chaotic idea to my collaborators—let’s kill PES Open Source, and start from scratch.

Why limit or affiliate with only our own college? Let’s instead individually seek out the creative and passionate people and create an invite-only community. A smaller community with a larger impact. Every member has the power to invite another person into our community. Invite only those we trust, so there’s always a chain of trust that can be followed to everyone.

This lets us keep the upside like the spark that led to our fruitful projects, and the thoughtful discourse. All started by the “good” members. We keep none of the downside, ie, dormant members in it for the wrong reasons.

Most importantly, we do not control or dictate the activities, or the direction of any of the members. Our job is to connect, not conduct. We create a large metaorganisation that houses many Units, ie, groups of collaborators for just about any activity. Units are fully autonomous. This also lets us accomodate existing groups of people who were doing things similar to what we are. A highly federated and decentralized structure that supports highly motivated people to connect and make potentially awesome things happen. This formed the basis for UniFOSS.

That’s where we currently stand. It’s still the early days, and even though I am only an year away from graduation, it feels like we are just getting started.

I strongly believe that the antidote to this dystopian society that debases learning is resistance. Resistance, not by revolt or being righteous. Rather, resistance by refusing to be satisfied with what is handed to us. Resistance by taking initiative and seeking what we truly deserve.

Appendix: The current struggle with diversity

We still face one challenge that confounds us to this day. We have done poorly with diversity. Most of our members, even after the transition are men, and people with plenty of privilege. Women and members of other marginalized groups in tech haven’t been participating in the same ratio as their presence in our college. We are hoping that our invite-only system lets us take affirmative action and choose invite people from more diverse and marginalized backgrounds.

If you are belong to a historically marginalized community in tech, or identify as a woman, and want to be a part of UniFOSS, please reach out to me at raykar dot ath (at) gmail dot com.